I’m trying my damnedest to rekindle the language I studied 30+ years ago. There’s a vague memory of stumbling through a Spanish oral exam and a less vague one of achieving only a 2nd class degree, so it might be that my memory of chatting like a native is a fond one. Even so, somewhere in the grey matter, there’s something to build on. One of the many things I love about this town, moreover this region, is that people don’t quickly revert to English when speaking to an obvious foreigner, so the Spanish has come on no end. I dated a staunch Galician nationalist for a while, who refused to speak Castilian Spanish, only Gallego or English. He looked like he might throw up every time I attempted to communicate in the language I was trying to revive but he despised. Once he’d disappeared from my Estribela life, and took his nationalism with him, I got back to doing what I wanted to: communicate with the people around me in a language that we all knew.

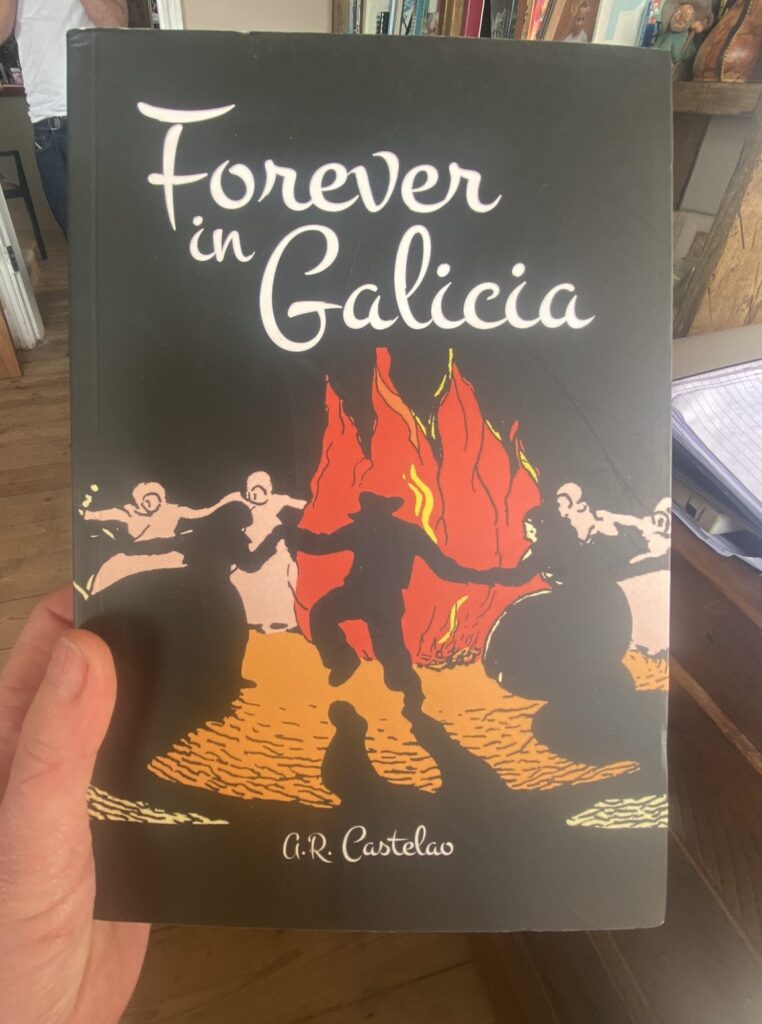

Most Galicians speak Gallego and Castilian too, but Castilian is prominent and the Galician nationalist movement tries to address this loss by promoting the Galician tongue and ensuring that the culture and language are not lost, as well as campaigning for Galician independence from Spain. If its good enough for the Basques…I love that locals move between both languages, and I’d love even more to learn the regional language, a blend of Spanish and Portuguese. I’ve picked up words and phrases, but accept that Spanish is enough of a challenge for now. I’m reading ‘Forever in Galicia’ (Sempre en Galiza) the seminal book by the father of Galicia: artist and Galician nationalist politician, A.R. Castelao, who wrote a political and personal memoir of the region he loved whilst exiled by the Lerroux government in the 1930s. Its an extensive reflection on Galician identity, and worth reading the only translation into English if you want to understand more about the place and the people here.

Since socialising with Spanish speakers, I have the most enormous respect for anyone coming to England and immersing themselves in our culture and language, often with out any appreciation about the sheer effort it takes. Granted, many countries learn English at school from a young age, the best time to absorb it fully. In my view, its an absolute failing that our school system mostly sees foreign languages as optional, leaving us happy to fall back on English in every situation and missing out on the essence of each country that we visit. However, immersing yourself in another culture and with native speakers is exhausting, however well-meaning your local friends. A few hours of socialising with my small but swelling Spanish and I am done. As my acquaintances will be, having to repeat every other sentence twice. Como? Cultural differences are also navigated. It seems that I’m not funny in Galicia. English dry humour is taken at face value, and doesn’t translate so well. Oof. A local friend tried to explain Galician humour by giving an example, leaving me straight faced and bemused, ‘That’s not funny.’ Yesterday, my neighbour laughed at a something I said, but it wasn’t a joke.

And so, I spend a lot of time here on my own which is new to me. Its unlike being alone at home, with friends and family always close by, even if I don’t see them. The ‘aloneness’ here has a sharp end, even with online chats being an option. I see my lovely neighbours every day; without them I could easily pass a week without saying a word to anyone other than in shops and cafes. I talk to myself quite a bit. This solo existence has taken some getting used to, and it took me by surprise at first, (although I’m usually here for two or three weeks at a time so we’re not talking strait-jacket levels of solitude). After close to twenty years of single parenting, with life moving at a mile-a-minute, I thought that all I really wanted was to have some ‘time to myself’, but it turns out that this requires some adjustment, and I’ve often thought when I’m here about those who truly don’t have anyone close, and how that must feel when there’s no end to it.

Even though I hardly know a soul, it seems that people know me. I had diner a while ago with a Galician friend and family, and the brother-in -law asked where I live. His parents are economic migrants and moved many years ago to St Andrews in Scotland to work at a Portuguese fish factory. They’ve never returned, although they still have a house in Cantoderea, the neighbourhood or ‘barrio’ next to Estribela. He spent some time in St Andrews with his parents when he was younger but didn’t fancy sticking around in the cold. To my utter surprise, when he last spoke to his mother, she recounted that her Galician friends were talking about ‘la rubia’ in the neighbourhood, a blond woman who was roaming around and new to the area. That was me, an Englishwoman in Estribela, moving along the grapevine between Galicia and St Andrews.

Thanks, David 🙂

Julia la rubia has a certain ring to it, it you ever need a Nom de plume!

This post has made me determined to actually learn some proper greek, everyone always slips straight into English and it’s all too easy. Before you know it 18 summers have slipped by ….